Art historian and writer Daria Lysenko continues to expand her literary footprint with her latest bilingual poetry collection “Я чув що, ти в Нідерландах…” / “Ik hoor dat je in Nederland bent…” out 16 June!

Daria is a published author in Ukraine and Croatia, and now the Netherlands, where she arrived in 2022 following the russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Alongside her work as a poet, Daria is a core member of the VATAHA team and a frequent contributor to the website. The publication of this bilingual collection was made possible through a generous grant from the Dutch Foundation for Literature (Letterenfonds).

In this conversation, we discuss Daria’s newly-published bilingual poetry collection, what it’s like to be Ukrainian in the Netherlands during wartime, and her experience adjusting to life abroad and the role poetry plays in that process.

What inspired your book and the title “Я чув що, ти в Нідерландах…” / “Ik hoor dat je in Nederland bent…”?

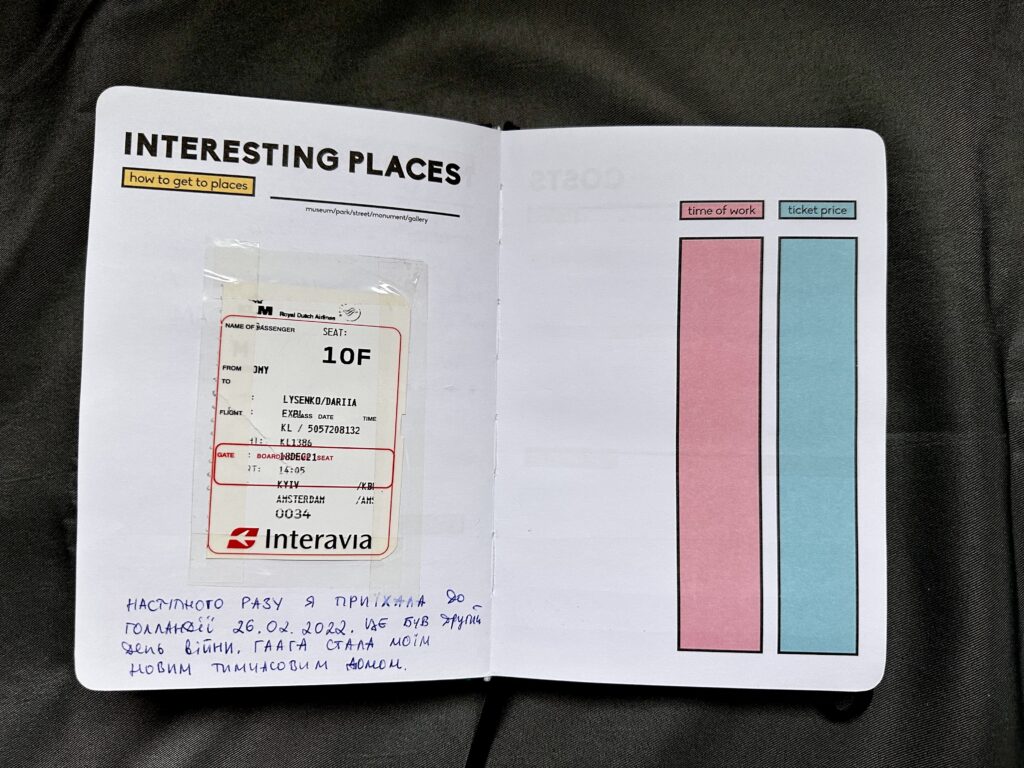

In short, the answer would be one word: support. When the full-scale invasion began in February 2022, I fled from Ukraine to the Netherlands, thinking that my arrival would be nonsensical, because as soon as I landed, a war of this magnitude should stop. It seemed simply impossible that such a war could happen in Europe in the twenty-first century. At the time, I thought it would last a few days at most—then weeks, and so on… Many people were going through the same thing. If you remember, the whole world was showing unbelievable support, which amazed me, because I thought everyone would turn away, just as they did in 2014 when the war really began.

Unexpectedly for me, from the first day of the invasion, absolutely everyone remembered me—close friends, acquaintances, acquaintances of acquaintances, and even strangers. My phone, different messengers, and email inbox were simply overflowing with words of support, offers of help, invitations to stay at people’s homes, etc.

I lived half my life in Croatia, in Zagreb, and some time in Belgrade, Serbia, and most of these messages were from there: friends and acquaintances who were concerned. And just imagine—almost all of these messages began with this phrase: I heard that you are in the Netherlands… One file on my computer remained with the auto-saved title I heard that you are in the Netherlands… And when I was looking for a title for this collection, it seemed to me that it was exactly what I needed. To be honest, even now, in my fourth year of living here, I’m still surprised that I’m in the Netherlands—it still feels unusual.

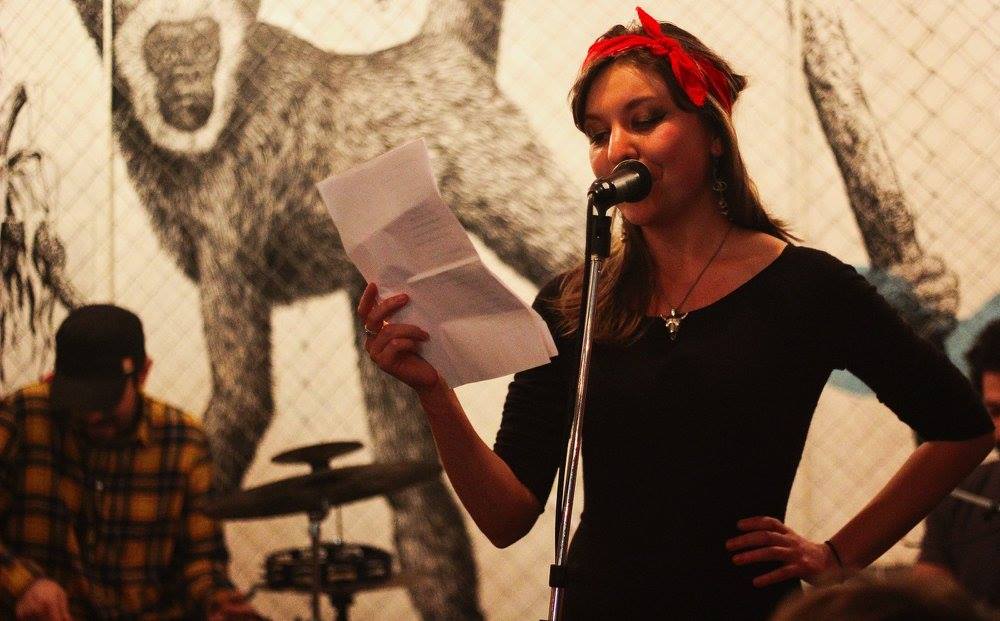

There was a lot of encouragement from my poet friends, who told me to write—just write what I see and feel. And this encouragement was well needed, because writing or making any sort of art, any kind of poetry, if you are not in Ukraine, not on the frontline, felt inappropriate, like you don’t have the right for it. Many poets still have some kind of internal taboo. It seemed like your experience is simply not important in all of this. However, I heard a lot of assurances that this wasn’t the case, and I decided to write for myself. Everything I wrote felt somehow off at first, but I timidly continued. The result is a kind of diary from 2022 to 2025, which chronologically shows—through my lens—what it is like to be a Ukrainian in the Netherlands during the war.

What was the thinking behind the overall design of the book: cover, layout, visuals?

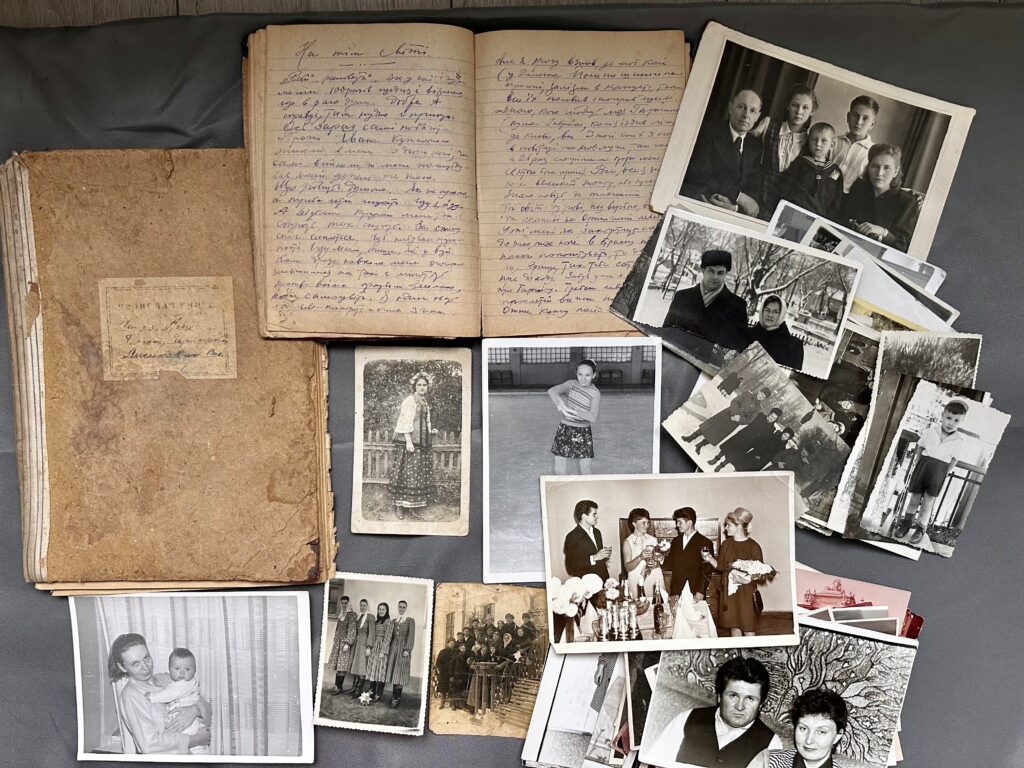

To be honest, it took me a long time to figure out what I wanted to see on the cover. How do you show a Ukrainian in the Netherlands? And how do you do it without stereotypes—clogs, tulips, windmills, and Ukrainian сlichéd folk kitsch? Finally, I remembered that when I left Kyiv, I had packed the most valuable thing to me—a folder with old family photos and my great-great-grandfather’s diary in my backpack. I looked through them, and the photo of the girl on the cover resonated with me. It is a 19th-century photo of one of my relatives, whose name was Daria. I was named after her because my parents really liked this photo of a Ukrainian girl from our family. It seemed to me that she could represent not only me, but Ukrainians in general, and the orange background matched the Dutch symbolic color.

Each book chapter represents a new year from 2022 to 2025. The colors are also important here, from the coldest to the brightest, as a symbol of life, movement forward, and getting used to the new reality. In addition to color, each section has a photograph that includes some element mentioned in the poems.

I have to say that the design of this book would not have been realized without my friend and artist Anastasia Prokofieva. The book may look minimalistic, but it was incredibly hard work.

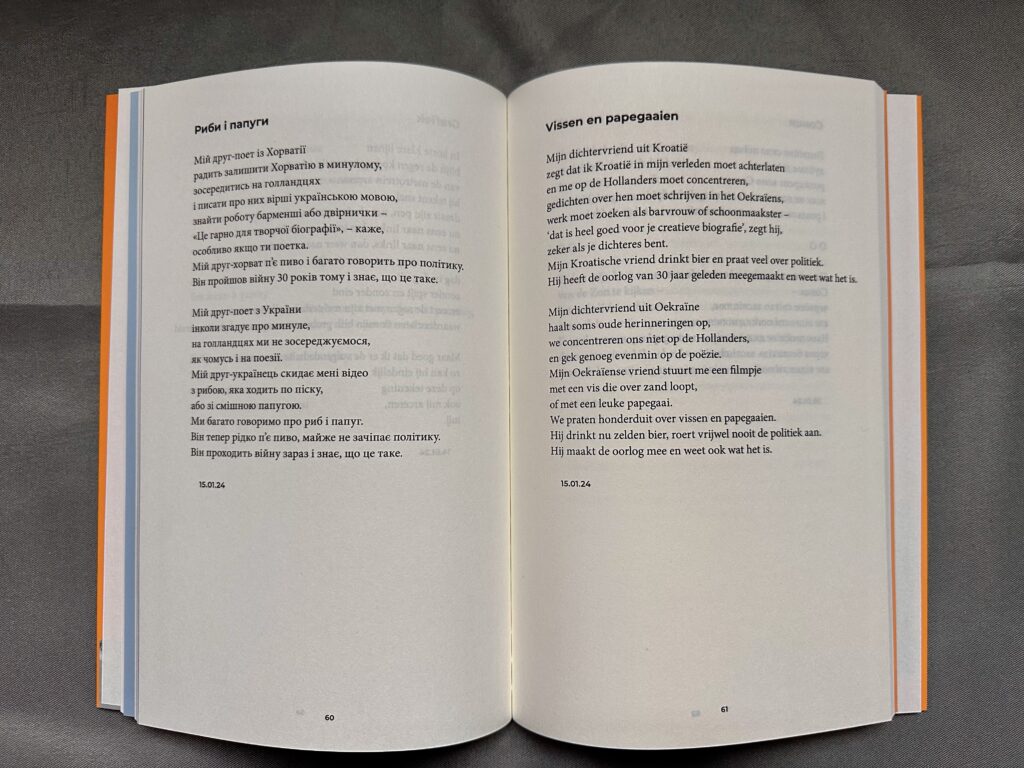

Why did you decide to make the poetry collection bilingual, instead of, for example, having it in Ukrainian and then translating it into Dutch?

When it came to the book, I knew right away that I wanted it to be bilingual. I wanted to tell the Dutch about Ukrainians, to destroy some stereotypes about us, and to show—through my own experience—what it is like to be a Ukrainian in the Netherlands today. But also, to show them their country through the eyes of a foreigner—which is always interesting. The same applies to Ukrainians in the Netherlands—we also had or still have stereotypes about the Dutch that need to be dismantled.

This book is about the rapprochement of two cultures, and both languages are essential. But it’s not only about that. I think that Ukrainian refugees will read these poems and feel: oh, this is about me. I’ve already received feedback like that when I posted some of my poems on Instagram. Sometimes, it’s important to feel that I’m not alone. At the very least, if poetry doesn’t reflect your state or your feelings, it just passes you by. I think people find solace in poetry when they find something that resonates. I hope to make the reader smile, at least.

Do you write with a specific audience in mind—Ukrainians, the Dutch, a wider international readership, future generations?

In general, writing poetry with a specific audience in mind is not a good idea. It’s useful when you’re writing a marketing post: there, it’s necessary. In poetry, it’s different—you write because you need to write. Everything else comes—or doesn’t come.

As I’ve said, this collection is about the acquaintance between Dutch and Ukrainian cultures, the erasure of stereotypes. But even though my poems feature the Dutch landscape, I think this collection could be interesting in other countries too. It’s about Ukraine and the war, about the refugee experience. For example, some poems have already been translated into Croatian and sparked interest among Croatian readers.

It would be immodest to assume that future generations will read my work, but as a document of this time, I think it will be interesting.

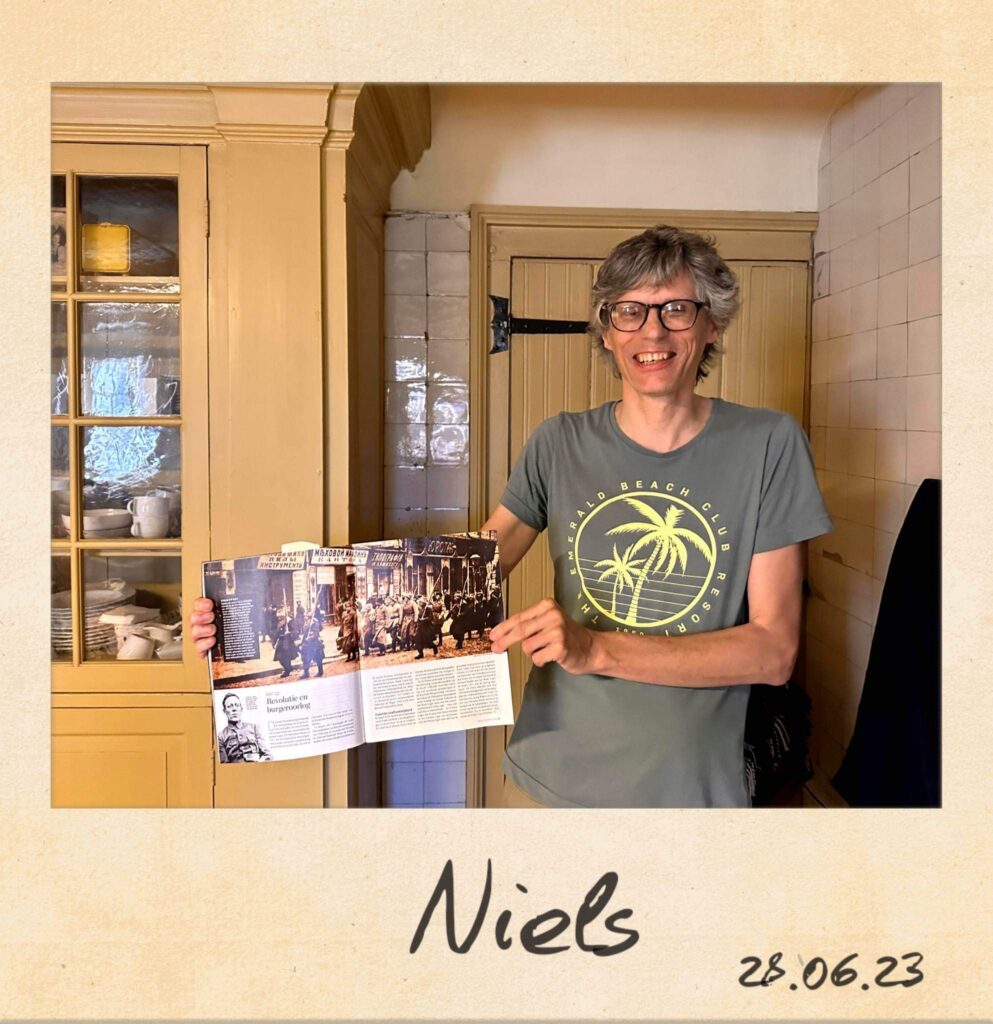

There’s a funny coincidence in how you found your translator: you’d written a poem about him before knowing he’d be the one to translate your work. Can you tell us that story and what it was like to collaborate on the book?

Yes, it’s a very unusual story. The poem Niels is based on a true story that happened to me. In the poem, my fellow volunteer at the Dedel Museum in The Hague—the protagonist of the poem—asks me if I know a Dutch farmer who lives in a village in Ukraine. He said the man had been on TV, so I must know him—because there aren’t many Dutch people in Ukraine. It was a very sweet assumption, but of course, I didn’t know this Dutch farmer.

Later, in order to find a translator, I translated several poems into English, including Niels. And then one day I received a call from a man who told me, “I am the farmer from the poem!” Can you imagine? I was just shocked that this was even theoretically possible. His name is Arie van der Ent, and he actually lives in Hermanivka, Ukraine, where he does a lot of translations into Dutch. He also writes himself and has published many books in the Netherlands. So thanks to Niels, Arie was already in my book before we ever met! I’m very glad that he became my translator, and I think he found the work of translation quite easy.

What challenges have you encountered in the process of publishing your work?

Actually, quite a few. To publish this book, I received a Letterenfonds grant, for which I was nominated by the VATAHA Foundation in 2024. Without this grant, the poems would have remained in the notes app on my phone. So I thought that having won the grant, everything else would follow smoothly. But as it turned out, Dutch publishers all refused to consider publishing a bilingual book. They said they would only consider it if I left out the Ukrainian original and included only the Dutch translation. This was against my vision, so I kept searching, and I was very happy when Woord in Blik turned out to be the publisher I wanted. In general, even with texts (and remember that every author needs an editor!) and a grant, publishing a book is not easy. But it is definitely worth the effort.

You once said, “How can you be a beginner if you have already published books?”—referring to your experience of moving to the Netherlands and being seen as a literary newcomer, despite already having an established career in Ukraine and Croatia. How do you navigate the feeling of starting over professionally in a new country?

I have a poem in my collection called Being New about this. It’s not about a literary career per se, but about the general feeling of being new in an environment. Like in Tetris, all your achievements disappear, and you have to rebuild yourself from the cubes and sticks you’re given. And all of it now also with the “refugee” label. Maybe it’s a silly comparison, but it really feels that way.

It is a bit unpleasant because I am a member of the Croatian Writers Association, I have books, publications etc. But how could the Dutch know that? Most of what I wrote was either in Croatian or Ukrainian. So it’s absolutely clear that I have to start in a new and different way here.

It’s not the first time for me—I’ve moved around a lot and often had to start from scratch. What has united these experiences is that I’ve somehow always been a kind of Ukrainian cultural diplomat. Even in Ukraine, where I worked in PR for the National Art Museum of Ukraine, or contributed to a project called Reading Kyiv as a co-author. Of course, the refugee experience is different—it’s not just a move. But still, at this stage, I see it as a privilege to tell the Dutch about Ukraine in Dutch—and through poetry, no less.

How has poetry helped you express or process experiences, particularly as a Ukrainian refugee?

I think poetry is the support that allows me to remain myself in this situation. I’ve always been a storyteller, a poet—the only difference is that I used to write about playful or even mischievous things, and now I write about less pleasant topics. That stability—when you write—is therapeutic. But honestly, if it weren’t for this question, I probably wouldn’t have thought about it.

An interesting observation was made by Lisa Weeda, a Dutch writer who wrote the foreword to this collection. In a conversation, she said she sees the first poems as more dry, while the later poems are vivid and full of life and metaphors. This reflects my psychological state—from complete numbness to a kind of normality.

What are your hopes and plans for this collection? What’s next for you?

I would really like the Dutch to notice this book. I’d like to spark interest in Ukraine and with Ukrainians not just because of the war, but simply because we have a lot in common. At the very least, because we live next to each other now. We have so much to talk about. I want to have that friendly dialogue—not in the context of “when will you return home?”, a question often asked of Ukrainians here, but simply about us here and now, about culture and literature. And, of course, about the war, because no matter what we write or talk about, the conversation always leads back to the war.

This is probably the first Ukrainian poetry book by a contemporary poet to be translated into Dutch (you won’t find any Ukrainian poetry classics in bookstores here either). That’s incredibly sad. I hope this starts a dialogue that will continue through future translations and other Ukrainian voices.

As for Ukrainian presentations for Ukrainians in the Netherlands, I believe they’ll go as well as possible—at least, I hope so. I have future plans, but I’m still considering the reality of making them happen 😊 I’ll just say that I have some prose texts in mind.

Anything else you’d like to share with our community?

Actually, my book is solid proof of how important support is—to stay afloat, to create, to be yourself and to be a support for others. Especially in times of trial like now. From the very first steps of writing these texts to receiving a grant, designing the cover, and printing—it was all thanks to people who supported me with words and actions. So every “You can do it!” or “Let me help you” can ultimately create more impact than anyone can imagine.

Pre-order your copy!

The book will be available for purchase online via the following links (starting 16 June), directly from the author on her website, or by messaging her privately on social media. Books will also be available for purchase at presentations.

Stay tuned for book presentations, both in Ukrainian and Dutch!