Lisa Weeda is a renowned Dutch-Ukrainian novelist, playwright, curator of literary programmes and multimedia creator. She is the Netherlands’ preeminent literary voice on Ukraine and was chosen as the “literary talent of the year” by De Volkskrant in 2022. Lisa’s first work, the novella “De benen van Petrovski” [The Legs of Petrovski] was published in 2016.

Her debut full-length novel “Aleksandra”, which was heavily inspired by her grandmother’s family history, was published to critical acclaim in 2021. Last year, Lisa followed it with her second novel “Dans Dans Revolutie.” Lisa is also a frequent collaborator of VATAHA, especially when it comes to all things literature.

Back in March, we sat down with her for a conversation about how her Ukrainian roots shaped her work, and reflects on working with VATAHA to bring Ukrainian stories closer to Dutch audiences.

On Lisa’s family history

Can you tell me about your personal connection to Ukraine and how it has shaped your work?

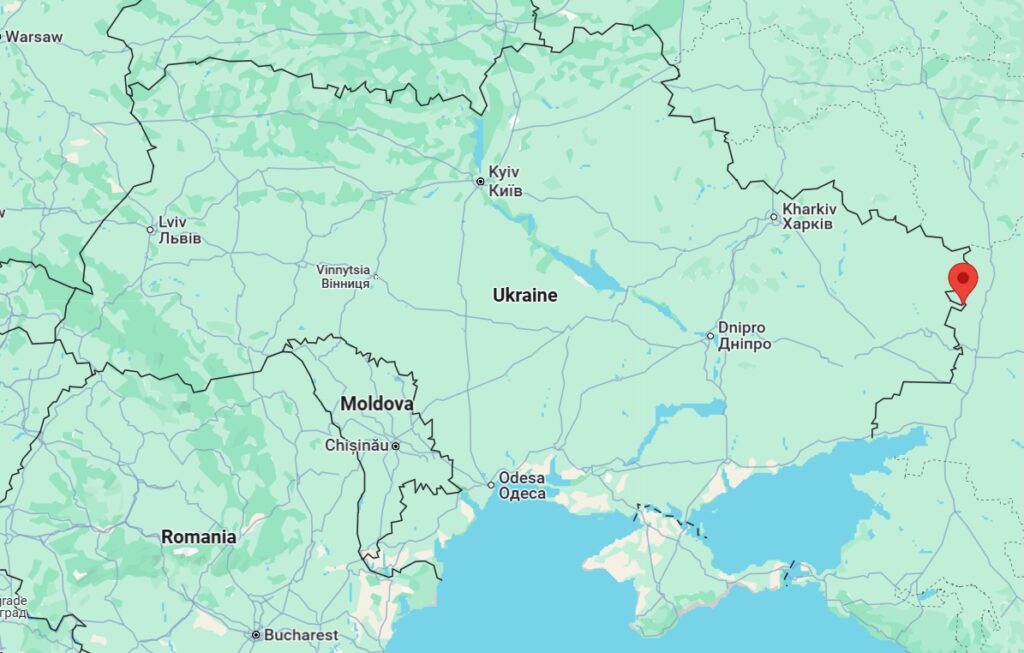

I’m partly of Ukrainian heritage. My grandmother was from a tiny village called Blahovishchenka, all the way in the east, literally right on the russian border.

It was literally a village of seven houses. She grew up in a family of Don Cossacks and farmers, partly Ukrainian and partly russian, which is obviously a complicated history now. But it is what it is.

Some of my family still lives in Ukraine to this day, in different parts of the country—Odessa and Luhansk. Since 2013, I’ve been researching my grandmother’s story. She was deported to Germany during WWII to work in a factory as an Ostarbeiter (German for ‘East worker’).

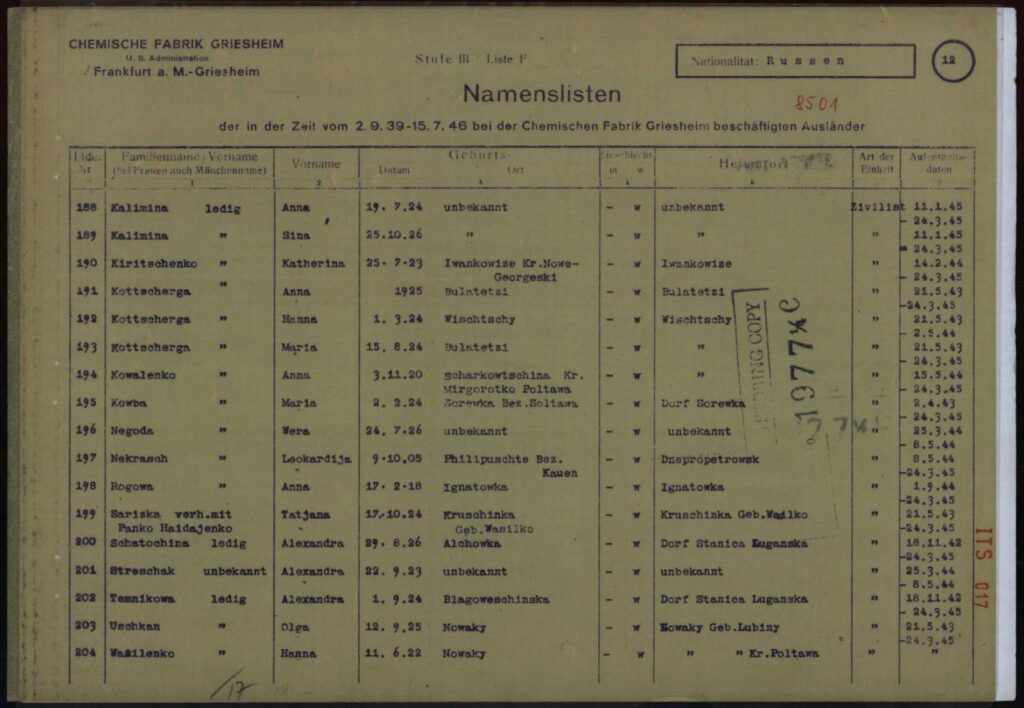

Just yesterday [March 19], I finally received a picture of her Ostarbeiter [German for ‘East worker’] ID card in Germany. It was sent by an archival worker I’ve been in contact with for five years. I’ve been looking for this photo for over a decade, it’s very emotional. My grandmother was 18 in the photo, and she doesn’t look very happy in it, but it’s been a big missing piece in my research. Until now, we only had one photo of her from 1939—nothing from before or during the war years. I knew that every Ostarbeiter girl had a worker’s ID with a photo. I just didn’t know where to look. This archivist found it in some kind of factory archive. It was such a missing piece. On the other page, it says where she was born, where she arrived, where she lived [in Griesheim am Main] where she was working, and when she entered Germany in November 1942 and when she left the country in 1945, but I never saw the picture of her from there.

In 2016, I spent a month in Ukraine traveling from Lviv to Odesa to Dnipro and Kyiv. I interviewed a lot of young people born after Ukraine became independent in 1991. That trip was part of the research for my novel Aleksandra. It covers a whole century of Ukrainian history: Donbas, Don Cossacks, kulaks, Holodomor, WWII, and the war that began in 2014. It’s a kind of magical exploration of the region’s complex past.

In the meantime, I also worked on a 13-minute virtual reality project that immerses viewers in the life of a woman from the Donbas region. She lives near the site where Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 was shot down in 2014, killing all 298 people on board, including 193 Dutch citizens. At that time, the region had already been at war for 97 days, but in the Netherlands, nobody paid attention until the plane came down and suddenly it became a crisis.

I’m very interested in perspective, how we tell stories from Eastern Europe, especially Ukraine, to people in the Netherlands or Germany. My books are now also published in German, which helps.

How did your connection to Ukraine and Ukrainian identity evolve over time?

At first, I felt very distant from Ukrainian history. My grandmother never really talked about her past. But family members from Ukraine would visit every year, and there was always a different language in the house, different objects, even different chocolate—drier, Ukrainian chocolate. That also felt normal to me.

My grandmother spoke russian, and though she had some Ukrainian friends, they were never part of our daily family life, just there for big birthdays. My grandfather insisted they speak Dutch at home. My mother was the first of her siblings to travel back to Ukraine with my grandmother in 1973, when it was still part of the Soviet Union. They took the train all the way to Moscow and then to Stanytsia Luhanska.

Later, the whole family went back, and my grandfather even met my great-grandmother. But I didn’t grow up identifying strongly as Ukrainian. Maybe my mom felt it more, but we weren’t a family that talked about heritage. In contrast, I think Indonesian families in the Netherlands have kept more of their heritage alive across generations.

For us, there was already a culture of silence. My grandmother grew up in the Stalinist 1930s—talking about your past could be dangerous. The only thing that remained was that she would always give me way too much food—something very Ukrainian. You could never say no. Dutch grandmothers would give you one small piece of cake and that’s it.

But that started to shift in 2014. In the summer of 2014 my grandmother’s sisters visited that summer for her 90th birthday. Around that time, just after the MH17 plane was shot down, I was at a party in Amsterdam and someone asked me if my family felt guilty about the plane getting shot down. I was stunned, why would my teenage cousin have anything to do with a missile? It made me realize how little people here knew about Ukraine.

I had already started interviewing my grandmother by then—recording little stories—but that moment made me realize I needed to do more. It wasn’t just about identity, it became a responsibility. Since 2022, I’ve appeared on Dutch television and radio as someone with a Ukrainian background, because otherwise the conversation would be dominated by Dutch pundits or others without any real connection to Ukraine. I felt I could bring both the political and the human perspective.

I’ve also traveled to Ukraine twice since the invasion and plan to go again to Lviv in April and elsewhere for a new project in July [2025]. I think it’s important to show that there are still people with a Ukrainian background, or even Dutch people, who are willing to go.

On current projects

What are you currently working on?

I was asked to write a children’s book about Ukraine last year. At first, I was hesitant. My agent was excited, but I knew how hard it would be to get it right. Ukraine is such a complex topic, and especially for kids.

But then I got matched with a brilliant illustrator—Olesia Sekeresh—who’s originally from Kyiv but now lives in Freiburg. She’s won several awards. Once we started working together, I said yes to the project.

So now I’m writing this children’s book for kids aged 8 to 12. It’s meant to be a beautiful introduction to Ukraine, not just politics, but history, culture, food, coffee, even mammoth bones! (There’s a real story about a guy in the 1960s who discovered mammoth bones while digging a cellar!)

We’re also including things like the history of Zaporozhian Sich, Yaroslav the Wise, the Sophia Cathedral… all kinds of stories. It’s not chronological, it’s more like an adventure through hidden treasures.

The storyline begins with my grandmother, who passed away last year aged 99. In a way, I want to explore this story together with her. It starts with a children’s game called “secrets,” where you dig a hole, hide your favorite things, and cover it with glass. This idea, which appears in a book by Oksana Zabuzhko, was also common in the 1930s to hide icons and valuables from the communists. Through these secret hiding places, the grandmother and child journey through Ukrainian history. They even meet Zelensky, who’s giving an interview in a metro station, and they visit one of the deepest subways in the world. It’s a huge project, and the deadline is in June, so it’s intense.

The second project I’m working on is called “Zerno” – “wheat” in Ukrainian. It’s about wheat and Ukraine, which is such a broad but essential theme when you talk about Ukraine’s history, imperialism, the Holodomor, and economic power. I was invited by a theater company in Assen that creates site-specific performances to write this piece.

I’m telling the story through three characters, all connected by one family and one wheat field across different time periods. The first is a man during the Holodomor whose farm is confiscated, and he dreams of endless wheat fields with only a few people left. It’s a story of loss and the erasure of freedom. The second character is a woman in 2022, during the full-scale invasion. It’s harvest time, and she must decide whether to stay or flee. In the end, she sets her wheat field on fire rather than let the russians take it. The third part is set in the future, focusing on the demining of Ukraine’s fields, in my opinion, an under-discussed issue that will affect the country for decades. I’m traveling to Ukraine in July to research this.

All of my projects seem to connect back to Ukraine, and that started with my family history. It’s become something I’m known for. Until recently I was the only fiction writer in the Netherlands writing about Ukraine. Now, people find me when they need someone to write or speak about it. For example, I was just asked to write an afterward for the Dutch translation of Victoria Amelina’s book [Looking at Women Looking At War].

I think I will continue writing about Ukraine because these stories need to be told. Dutch readers need to discover Victoria Amelina, Andrey Kurkov, Serhiy Zhadan, and the many poets and writers emerging now. There isn’t enough translated yet. I try to serve as a kind of bridge keeping Ukraine visible, but I only write what feels genuine to me.

But still, it all began with my grandmother’s story. As I mentioned, she was an Ostarbeiter, one of over a million Ukrainian and Belarusian women that were taken to Germany for forced labor during WWII [writer’s note: official estimates are even higher]. In the Netherlands, the word “deportation” almost exclusively refers to Jewish history. That’s a crucial history, but the Ostarbeiter story remains largely untold here. Even in Germany, only recently have monuments been erected for these women.

Starting from my grandma’s story, I discovered other overlooked histories, like the Executed Renaissance. That’s the story I’m weaving into my next novel: it’s about a father-daughter relationship where the daughter travels back in time to save the manuscripts of writers from the Slovo Building in Kharkiv. Of course, it’s symbolic and impossible, but it’s really about preserving Ukraine’s literary heritage.

There have been some discussions about translating my work to Ukrainian. Aleksandra has already been translated into French and several other languages—eight in total, which is quite a lot for a first book. I’m really proud of that. But for now, I’d rather go to Ukraine, gather new stories, and bring them back to the Netherlands than bring my own book to Ukraine. It’s not a priority at the moment.

If that’s my task for now—to bring Ukrainian history to Dutch readers—I’m fine with that.

On Work with VATAHA

How did you get involved with VATAHA?

I think I met [VATAHA’s co-founder] Oksana in 2023, maybe at a performance in Schiedam, at a bookstore. She was there, and I think we’d already spoken before online. That was a hectic period in my life—post-full-scale-invasion I was working nonstop. It felt like during that period Oksana just kind of appeared and never left. I knew she was running VATAHA. I travel a lot, so I can’t always be physically present, but I really wanted to help however I could.

I’ve been a literary programmer for ten years, so I know how to ask the right questions to shape a good event or program. I’m quite detail-oriented. And it’s just great to work with a team of young Ukrainians focused on culture, not only politics. I follow the news, I write about it, I talk about it, but if you do that every day on a personal level, it consumes you.

Is there something in particular you’re looking forward to doing with VATAHA? You mentioned literary work?

First, I actually want to try training for the “Run for Ukraine” in Bucharest. I used to run when I was younger, then stopped for a long time. I picked it up again a few months before the invasion—and then everything fell apart. Nothing made sense anymore. But I’d like to start again and be part of the run. That’s one practical thing.

Also, whenever people ask me how to connect to Ukrainian communities, I always say: go to VATAHA, talk to them. I try to help however I can. For example, I helped Daria Lysenko with some editing and advice on her poetry and wrote the foreword.

More people recently received funding through a Letterenfonds grant, and I’m trying to push writers toward publishing houses. But it’s hard. Dutch publishers are still quite closed to Ukrainian literature. There was a kind of shallow “Ukraine hype” after the full-scale invasion, but by now it’s over. So I’m thinking of other ways, like bringing writers to stages, highlighting their voices differently.

What I think is so important about VATAHA is that VATAHA tries to reach Dutch audiences in a really specific way, which can be incredibly challenging. For a long time, they’ve had this very stereotypical image of Ukraine. It’s like trying to condense 100 years of Ukrainian history into three years and say, look, this is a different country. We’re modern, educated, literate. We have this incredible culture. I think VATAHA is helping create “Dutch memories” about Ukraine, making it more real and personal for Dutch people. That’s very valuable.

Read more

- Grab tickets to Lisa’s upcoming play “Graan/Zerno” in Assen from 1 to 19 October: (showings with English subtitles available!)

- Check out Lisa’s Dans Dans Revolutie installation at ILFU International Literature Festival Utrecht (30 September to 3 October)

- Check out Dans Dans Revolutie at Het Nationale Theater from 19 to 23 May (only few tickets remaining!)

- Preorder “Mooi boek over Oekraїne”, out 29 January 2026

- Check out Lisa’s website