I first encountered the work of the United Ukrainian Theatre at De Balie in Amsterdam, during a performance of Chaos back in July. Right off the bat, I was intrigued by a list of existential questions handed to the visitors as they entered the theatre: How do you know when you’re stressed? What has been the most difficult or surprising challenge about living in a new country? What does your support circle look like when you feel overwhelmed?

Her play unfolded as an attempt to answer those questions. Performed by a team of Ukrainian actresses in English, it began as a dark comedy before turning into a deeply emotional meditation on trauma and resilience. After the performance, the creative team joined a psychologist from the Empatia program on stage to speak candidly about mental health and the personal experiences behind the story.

That evening, I met theater director Yasha Gudzenko for the first time and was impressed by her candidness and resilience. Now based in the Netherlands, Yasha continues to create and collaborate through the United Ukrainian Theatre, a foundation she co-founded to bring together Ukrainian and Dutch artists and to nurture new creative talent in exile.

On Theatre

What draws you to theatre directing?

Sometimes you don’t choose theater — it chooses you.

My great-grandfather worked in theater, staging operas, so maybe it’s in the blood. I always wanted to go into this world but thought it was impossible: too corrupt, too competitive, too full of nepotism. But that turned out to be a myth. I got a scholarship to attend the Karpenko-Karyi University [in Kyiv] and studied under incredible teachers who not only taught us the craft but also built our confidence.

My directing mentor Oleg Drach made me believe in myself. That was magic, it gave me wings. My mentor used to tell us never to judge and never to “freeze” creativity in a final version. Theater, he said, should always stay alive. Even after a premiere, I might return to a play a month later and say, “Let’s redo the last two scenes.” It’s a living organism, not something to be embalmed. That’s the beauty of it — it’s the opposite of perfectionism.

Theater is the ultimate blend of art forms — film, poetry, music, dance — all in one breath. That’s what I love most about Ukrainian actors: they can do everything. Singing, dancing, fencing, juggling, martial arts — Ukrainian training is all about flexibility and imagination. Our actors are like Spider-Man: they can do anything. For me, theater is about curiosity, both for the audience and the artists.

I’ve also dabbled in film, but it’s not my medium. Film is the art of editing; theater is the art of presence. When I enter a theater space, I can’t switch off. I immediately start imagining what I’d stage there, how I’d shape the light, how I’d move the actors. With film, that doesn’t happen. Theater is where my creative energy truly flows.

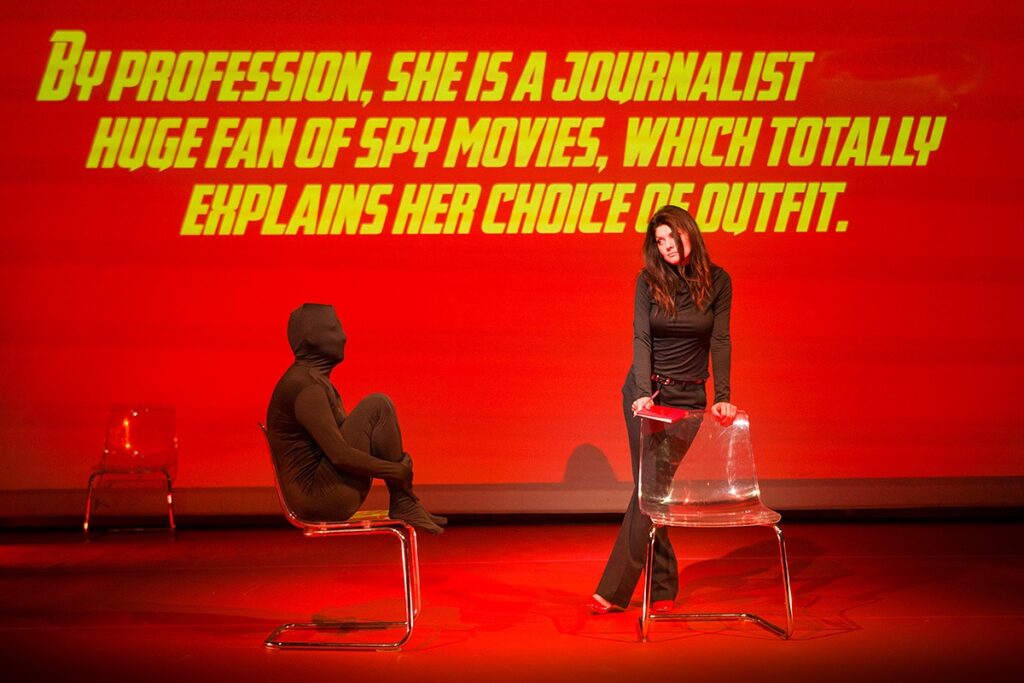

And when you build theater abroad, often from nothing, it’s even more special. I once dreamt of a red floor for one of my plays.In Ukraine, that was impossible. Here [in The Netherlands], I found the perfect chairs and props at IKEA for twenty euros. It felt like fate.

Are there downsides to working in theatre?

Of course, theater isn’t perfect. It can also be toxic — full of humiliation, abuse, and harassment. You’ve probably heard about the recent scandal in Ukraine: director Andriy Bilous was removed after students accused him of sexual misconduct. Around twenty-five cases came forward. It’s horrifying, but I deeply admire those who spoke up. The theater world lost a lot but it gained something far more important: truth.

Power in theater can also be dangerous. Some people use it to humiliate others, to feel significant. I’ve experienced that myself. Once, on a Ukrainian film set, I was treated terribly. After two weeks, I quit and promised myself I’d never work in that kind of environment again. That’s why now, when I work with my own team, who are mostly women, I really value mutual respect. The difference is enormous when the atmosphere is healthy and creative.

Your play Chaos is in English, but your work in Ukraine was predominantly in Ukrainian. Was it difficult to adapt to a new language?

I already have some experience with multilingual ensembles. For me, language is just a tool. Right now, I’m preparing my first project in Dutch, with a cast of Dutch actresses. I’ve also worked in German theatre and created a production in Sweden with a very international cast with four international actors. My experience as a casting director in international projects in Ukraine also helped.

With the Ukrainian United Theatre, we decided early on that English would be our main language for the performances. Some of the actresses had only just started learning English here, so the goal wasn’t perfect fluency, it was about accessibility and reaching a wider audience. In Amsterdam, most people are comfortable with English, so language isn’t a barrier. I’m even thinking it could be interesting to integrate Ukrainian snippets with subtitles, letting actors speak their native languages in certain scenes, since in the Netherlands, watching content in the original language with subtitles is completely normal. For me personally, I need to hear my own language to process it fully. In Chaos, there were Ukrainian subtitles alongside the English dialogue.

But unfortunately not all theatres can accommodate subtitles. Some smaller venues don’t have the space or equipment, which is why we aim for simple, clear English to ensure accessibility. Our focus is on comprehension rather than accent perfection. After all, the play is about expats so their English isn’t supposed to be perfect.

Who is your target audience then?

There are big cultural differences between Ukraine and the Netherlands, so pleasing everyone isn’t possible or necessary. Like with Ukrainian food that wasn’t widely available before the full-scale invasion, interest in Ukrainian culture can be generated even if none existed before. If you create from the heart, and those who are interested will find you. The goal is simply to make something that feels right.

On Chaos

Where do you usually get the scripts for your productions?

I write my own plays, but not of my own volition. Good text is the basis of any creative process, film or theatre. It’s not a guarantee of a successful production, but it is a pre-requisite. But good stageplays are expensive. Once again, I am very lucky in that regard. I managed to obtain the rights to two scripts by a Ukrainian playwright Sasha Denisova. But normally, as a Stichting, we can not afford to do so.

Nevertheless, I enjoy writing scripts. I am currently working on a recipe for a successful coup d’etat, an instruction manual for a revolution. It’s supposed to be abstract, not set in any identifiable country. I like political theatre, but going back to my earlier point about the lack of Ukrainian men, my options are quite limited. I work with three actresses, and therefore I end up having to be creative with my scripts or staging.

Chaos was a different story. We started out with an existing script but to be honest, it was really bad. So in the process of staging it, I had completely reimagined and rewritten the original script. And still, I wouldn’t say that the script is the strongest quality of Chaos. It relies on its interesting form and acting, which I focused on as the staging director. About a week before the premiere, we were still missing about 30% of the script. And it’s not like we had everything but were missing the ending, no. There is still so much room for improvement. It’s like a puzzle where you could still fit more pieces.

How did you work with color to make Chaos such an emotional and impactful production?

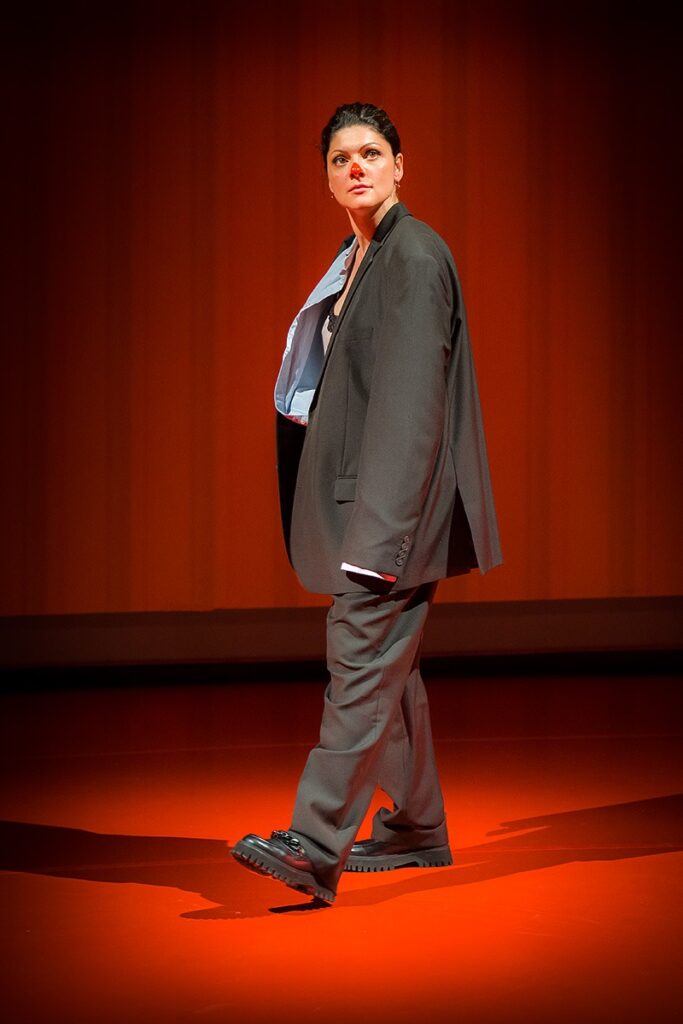

At the start of the play, we played a black-and-white video to reflect reality, contrasting with the theatrical red space on stage, a nod to David Lynch’s “Red Room” in Twin Peaks. Red conveys intensity and emotion. Costume color indicated character development: for instance, the teacher starts in red, moves through black, and ends in white, signifying a journey toward enlightenment.

Costumes are a key storytelling tool, even in minimalist settings. For example, a scene intended to provoke with revealing dresses sparked discussion and added layers to the narrative, despite initial resistance from the actors. In theatre, clothing can define character, mood, and context, especially when stage design is minimal, which is the case here.

How did the themes of mental health and trauma come to be part of Chaos?

The idea to incorporate mental health awareness into Chaos came gradually. The original text didn’t have any conflict, so we created a new character to reflect the internal psychological trauma and turmoil.

My actresses and I are all in therapy. We were all working through our own traumas. During rehearsals we talked a lot about that and that’s how the idea to include this message in the play. Because once you understand how to work with your own mental health, you can also start helping others who are struggling.

I know this from personal experience as someone who once drove herself into depression. For my family and me, that moment came after we had already gone through the first trauma of leaving our home, our ordinary life. When you witness everything, hear everything, live through it, those emotions stay with you. You’re not prepared for them. I wasn’t ready for things like buying a bulletproof vest for a student of mine in Ukraine and then suddenly finding out that he’d been killed. You store all of this inside, and at some point it overwhelms you completely. That chaos sneaks up gradually.

When I first came to The Netherlands [after the full-scale invasion], I had so much energy and tried to distract myself: I went on dates, bought clothes, and lived as if life was a party. And many people did the same. You don’t even realize you’re under stress, you think if you buy a new dress and drink a glass of wine, everything will be better. And then one day it all catches up with you.That’s why I understand it so deeply, it’s my own experience. Climbing out of that pit is hard. Many of my friends who returned from service had severe PTSD. They couldn’t live without medication. After going through courses of antidepressants, they slowly started to rebuild their lives. Sometimes antidepressants literally help people survive. Their brain chemistry literally changed and it’s a miracle that someone invented these things. But people are still afraid to ask for qualified help. They’re afraid of being seen as “crazy.”

And let’s be honest — in Ukraine, we don’t always distinguish between a psychologist, a psychotherapist, or a psychiatrist. Or we turn to coaches who promise “success and positivity,” when in fact you’re still in survival mode, trying to piece your life back together. I went through that too. You’ve lost your world, and someone tells you, “Come on, think positive!” But how can you, when you’re living in a shelter and sending job applications for weeks without a reply?

A friend once told me that after he buried his wife, he couldn’t focus, he moved through life like in a fog. That’s when I realized that we all buried our lives. No matter what kind of life you had in Ukraine, even if it wasn’t perfect — it was yours and you’ll still grieve it. You walked familiar streets, spoke your language, had your circle of friends. And if you had a good life in Ukraine, that loss is even harder. You can get your dream job here, have thirty-five kids with a Dutchman, even get a Dutch passport, but the grief will stay.

Can you tell us a bit more about your own mental health journey?

I was recently diagnosed with ADHD, something I had never realized I had before. Life in Ukraine was different, I never noticed it because being hyper-focused was normal, even useful. But here in the Netherlands, I had to learn a completely new system and understand how to live with it. If I had known earlier and been more aware of these things, my life here during these three years would have been of a completely different quality.

And honestly, I don’t know anyone my age who doesn’t go to therapy. Almost all of my friends do. People in my generation really take care of their mental health and I think that’s amazing. It’s the future. I think self-care should be taught in schools: how to deal with stress, how to manage emotions. If we started teaching that to children and adolescents, we’d have a society full of healthy people.

That’s where our collaboration with OPORA/ Empatia came in. I know the project manager, so we thought: why not combine efforts and make this message about mental health accessible to audiences who might be looking for psychological support?

OPORA helped us a lot with information support, social media posts, ticket sales and organizing the “ talk” after the performance. It was a very interesting experience. We noticed, though, that most Ukrainians left right after the show, and it was mainly the Dutch and international audiences who stayed for the discussion. That was quite telling, because Ukrainians aren’t used to giving feedback right after a performance or opening up about their feelings.

To conclude, what does theater mean to you?

Theater keeps me grounded — it’s alive, unpredictable, and endlessly human. It’s where I always feel happy. It can exhaust you, frustrate you, even hurt you, but it also gives back so much more than it takes.

There are moments when I wonder if I should do something else, something more stable. But then I step into a rehearsal and time stops. Theater rejuvenates you. It’s like a drug — the moment something that existed only in your imagination comes alive on stage, it’s incomparable.

This interview was conducted on July 24, translated from Ukrainian into English, and edited for clarity.

Next month we will publish Part 2 of this interview, where Yasha Gudzenko explains the inner workings of Dutch theater financing.