Ukrainian contemporary artist Marfa Vasilieva wants to set a Guinness World Record: create the largest hand woven carpet in the world. So large, it can fill the entire Dam Square in Amsterdam.

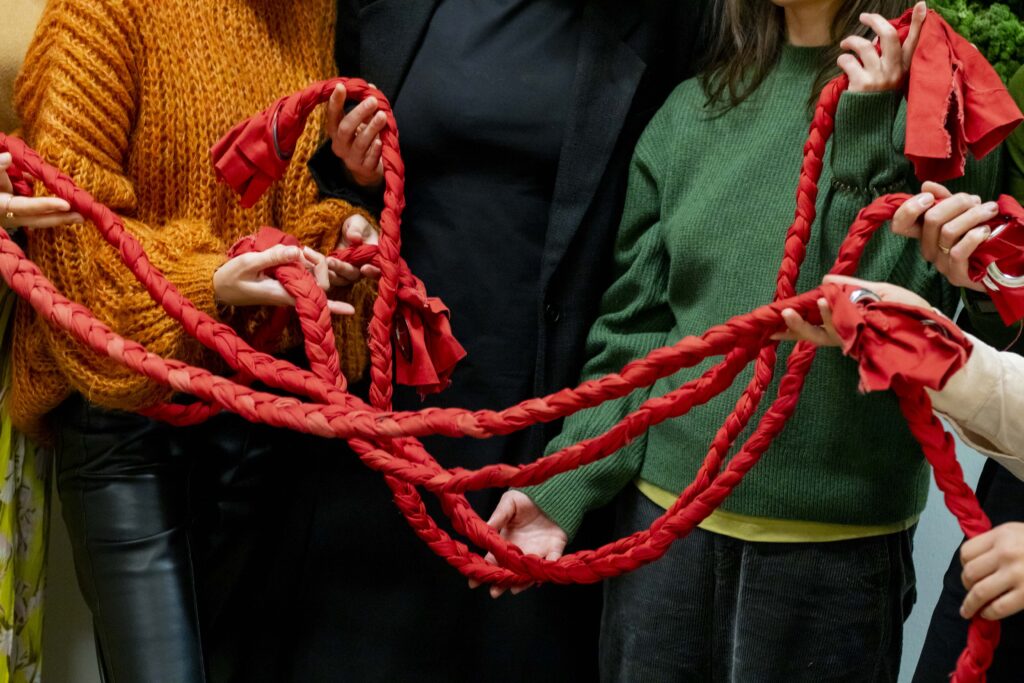

Her social art project is a participatory memorial which invites Ukrainians all over the world to weave red and black braids, where each braid represents someone’s life story, symbolizing love and mourning, to honor those affected by the war in Ukraine.

In this article, she shares her pain, learnings and vision for a world in which Ukraine’s deep sacrifices are braided into memory.

This piece was born from deep emotional processing. After I completed the Motonka project in 2022, where I worked with over 100 Ukrainian women who fled the war, I was left with not only the stories they shared, but also physical remnants: red fabric strips we used. That project shook me to the core. The weight of those stories stayed with me.

In 2023, I felt burned out, but in hindsight, I think I was actually in mourning. Trying to digest the collective grief of my country, the violence, the erasure.

Those leftover strips sat in my storage for months. I was thinking to throw it away, but something stopped me. I braided them instead. And then I just… looked at them. For days. They lay on a chest in our home, these long red braids, and I kept asking: what’s next? What do I do now?

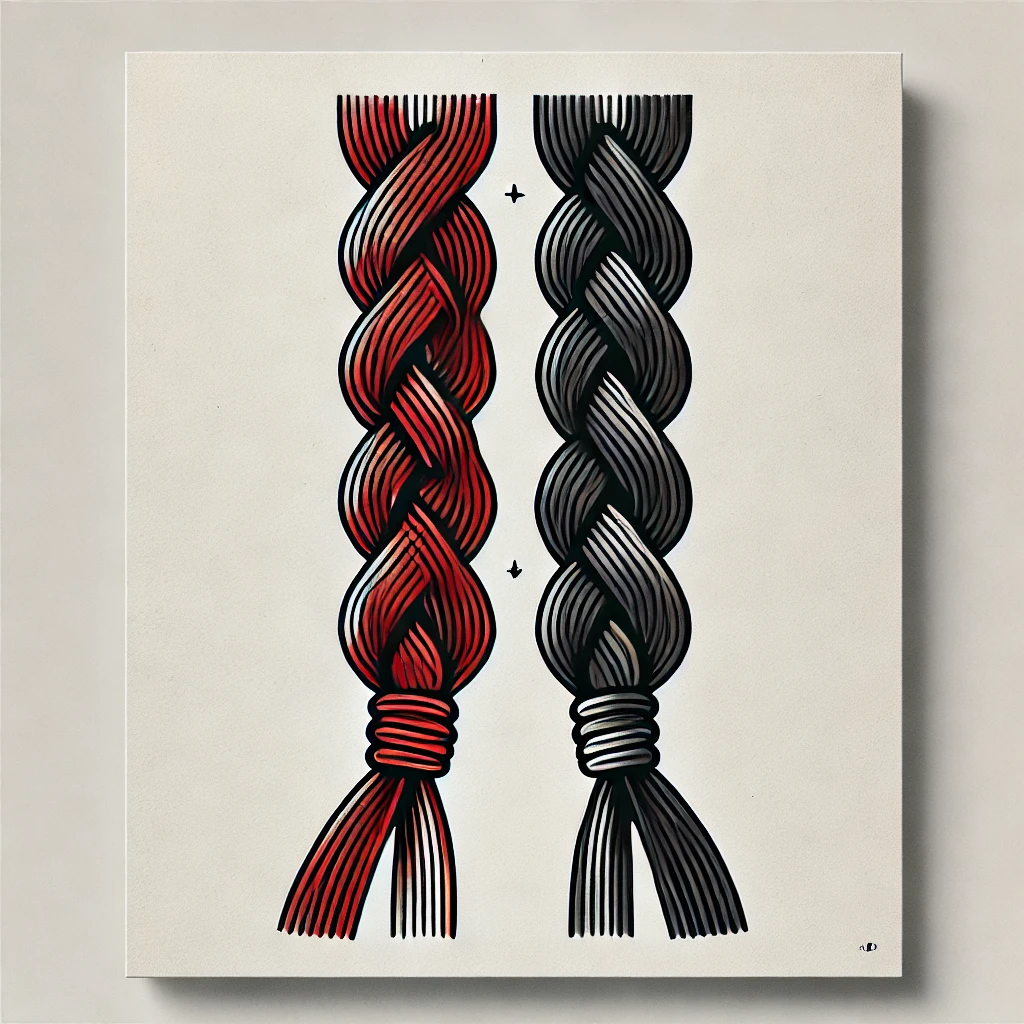

Then a song appeared in my head, Ukrainian song about two colors. We Ukrainians know it very well. The Ukrainian song “Dva Kolory” (Two Colors) became a quiet anthem of identity. Written in the 1960s, it tells of a mother’s embroidered Rushinik (a special symbolic towel) in red (for love) and black (for sorrow). It is a poetic code for Ukraine’s spirit. The Soviet authorities were uneasy with its message, fearing it stirred national sentiment.

The song lived on in people’s hearts as a gentle act of cultural resistance. As I listened to this song, looking at the red braids, I realized: I have love here. What’s missing is sorrow. That’s when I understood I needed to braid black braids, to tell the full truth. Just like in vyshyvanka, our traditional embroidered clothing, black and red, are sacred symbols of life, death, passion, and mourning. This symbolism gave me the language to begin.

Carpets are sacred, ceremonial.

This one is emotional, collective.

At some point, the title came: Carpet of Love and Sorrow. It came from what I wanted the piece to hold – love for the people who resist, who survive, who grieve, and sorrow for what we’ve lost. A carpet, to me, is a place where people gather. In some cultures, carpets are sacred, ceremonial. This one is emotional, collective. It carries the imprints of hands and hearts.

The idea became clearer: I wanted people to braid together, to bring grief into physical form. The Carpet gives space for shared mourning.

I was also inspired by Dora Maar, not just as Picasso’s muse, but as the woman who urged him to create Guernica. Her moral clarity touched me. I wanted to claim that same right: to speak through art about what’s unbearable. I see The Carpet of Love and Sorrow as my Guernica. A living, expanding protest against nazism, imperialism, and silence.

Too many braids, not enough braids

“How do you feel about the amount of braids you have collected? If you have too few, do you feel sad that not enough people participated? But perhaps you feel even sadder if you have many braids because of what each braid represents.”

That’s a powerful question, and honestly, it cuts right to the core of what I’ve been quietly grappling with.

We’ve collected thousands of braids so far during protests, workshops, and private meetings. But instead of rushing to count them as numbers, I started to shape the piece visually, emotionally. For PR purposes and to visualize the future Carpet, I began building the first square 1,5 meters x 1.5 meters. Think of it as a single “tile” of a larger, growing landscape. Many more will follow. Each square becomes a fragment of the whole, a modular grief, a collective whisper.

Some people cried as they braided.

Others were silent but trembling.

When I first began assembling the pilot square, I traveled to Rotterdam to collect some of the earliest braids. I intended to mix red and black, red for love and resistance, black for loss. But I couldn’t do it. I found myself unable to touch the black braids. They scared me. I was shocked by how many more black braids we had compared to red. And as a person, facing that imbalance, it broke me open.

There’s something profoundly heavy in those black strands. They carry grief that’s not just metaphorical: it’s real. People braided them while mourning friends, siblings, parents, children. Some of them were crying as they braided. Others were silent but trembling. And now, these braids live and look at me in this quiet dialogue with me. Every time I touch them, I feel that silence, not emptiness, but presence. This is what I want the viewer to feel too: an unspoken truth. Life stories that stares back at you.

This project is slow. It’s not something I can rush. It’s a long commitment, and it’s the first time in my life I’ve stepped into something this vast. That’s why we’re building a clear strategy now: how to scale it, how to engage the diaspora, activists, people in Ukraine, and allies around the world. The Carpet of Love and Sorrow is war memorial and historical inheritance, a living protest and a place for collective resilience.

As for the Guinness World Record, yes, we’re in conversation with them. If all goes as planned, we hope to break the record in about two years. We are looking for funding for this project and want to show it to the world in museums and public places. The shape of the piece will be made from lots of squares, so it can be transported easily. I want to go with it to Guinness World Record, to create something lasting: a trust fund and scholarship network for Ukrainian orphans affected by the war. A way for them to study in the best universities around the world, to rebuild their lives with dignity and hope. Because education is resistance too. it’s our long-term weapon against destruction.

This is not just art. It’s my whole heart. It’s diplomacy through thread. It’s grief woven into form. And when people ask me what my next art project is the answer is simple: this is it. It’s all of me, for now. I’m working on the book that will be a part of Capet of Love and Sorrow project, they will include war losses map. And I will keep going until The Carpet covers Dam Square. Until the world cannot look away.

And when doubt creeps in, when everything feels too dark I remember what Vita Kovalenko, a Ukrainian activist in the Netherlands once told me: “Even in dark times, we just need to stand up and do everything we can. So when we die, we know we did everything.” That keeps me going.

The braiders’ voices

The most common and most powerful feedback I receive from Ukrainians is that they cry while braiding. And to me, that is the greatest success of this project. Not because I want to make people sad, but because so many of us haven’t had space to feel.

We’ve been surviving, supporting others, running, rebuilding. But grief? Grief has been locked deep inside. People have come up to me after a session and said, “Thank you for today. I haven’t cried in years. I just couldn’t.”

That, to me, is why The Carpet of Love and Sorrow exists. It creates a quiet permission, a sacred moment to grieve. Together.

Because when we grieve together, we remember that we’re not alone. There’s something deeply healing in seeing someone else cry beside you, to know that your sorrow is mirrored, held, witnessed.

I want the audience to feel it in their bones: the cycle, the spiral, the scream we keep recycling across generations.

The feedback from Ukrainians is incredibly tender. Sensitive. Often, people whisper thank you with trembling voices. They say they didn’t expect to feel so much. Some tell me that by braiding, they could finally honor their emotions. That they felt more connected not just to others but to themselves.

With some of them we talk about cities that are alive in their cherished memories. Cities that are gone already. This journey via ruined cities of memories are unforgettable and beautiful.

One of the hidden intentions of this project is to help us turn compassion inward. As Ukrainians, we often carry deep empathy for others, but not always for ourselves. Through this simple act of braiding, of crafting with emotion, I hope people begin to see their own pain as sacred. As worthy of time. As part of love.

Beyond the Dam Square

In the future, I would love to do a theatrical collaboration: performative, emotional, alive in the spirit of Pina Bausch. Not theater in the traditional sense, but ritual movement. Paint. Silent dialogue. A lived choreography of war, migration, motherhood, exile. A mirror of how humanity keeps returning to the same heartbreak, century after century how we burn, rebuild, and forget. Uroboros that bites its tail. Humanity repeats itself. I want it to be intimate and hit the viewer with a strong message. A stage made of soil and canvas. A story that can’t be told in words alone.

I want the audience to feel it in their bones: the cycle, the spiral, the scream we keep recycling across generations. This will be a work that merges performance with visual art, archival memory, and sound effects.

And this September, the thread takes me to Japan. There, I’ll continue braiding with the Ukrainian community, carrying the ritual across continents, threading our collective grief and resistance into new soil.

I would love to exhibit at Burning Man,

the Tate Modern and the MOMA.

This September, I’m traveling to Nakanojo Biennale, Japan as a participant and to the residence. We will exhibit and evolve our long-term work: a series called Takamagahara (Heaven), which combines photography and body painting. This project we do with my art partner, Yoshiyasu Tamura, draws directly on women’s bodies in a manga style, reimagining archetypes from the ancient main pantheon of deities.

I was asked where I plan to exhibit my work in the future and while this question assumes the project is already finished, The Carpet of Love and Sorrow is still in process. I’m currently working with a team and an art producer to shape its future.

That said, I would love to exhibit this piece in the following institutions: Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam), Centraal Museum (Utrecht), Museum Arnhem, Eye Filmmuseum (Amsterdam), Framer Framed (Amsterdam), Tropenmuseum (Amsterdam), Het Nieuwe Instituut (Rotterdam), Tate Modern (London), Centre Pompidou (Paris), Palais de Tokyo (Paris), MoMA PS1 (New York), Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum (Hiroshima), Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), Documenta (Kassel), Venice Biennale (Venice), Berlin Biennale (Berlin), and Manifesta (various European cities).

I would also love to bring it to Burning Man, and to take it on a tour through villages and places where people don’t expect to see art at all. I grew up in Kyiv and was lucky to share an apartment with extraordinary people, one of them, Oleksandr Suprunets, developed a BIG IDEA that eventually received support from the Goethe-Institut. He created programs for small towns and villages across Ukraine, bringing artistic experiences to places that often get overlooked.

That inspiration stayed with me. I would love to continue that spirit because actions like this bring questions to minds. For people who may never visit MoMA or the Stedelijk, seeing art in their own environment can shift their whole sense of the world.

Marfa Vasilieva is a contemporary artist with a self-taught background in photography, painting, illustration, and photo-therapy, She was born in the USSR, grew up in an independent Ukraine and is now based in Amsterdam.

Her photography illustrates the truth, beauty, and depth of human emotion through thoroughly planned compositions. Her previous works have exhibited in Ukraine, The Netherlands, and Japan.

In this article, she provided her views on a list of interview questions, and we edited her responses for clarity.